In 2017, Time released its annual list of the 100 most influential people in the world (2). Among the usual assortment of entertainment personalities, politicians, and various thought leaders, one name would stand out as a particularly noteworthy inclusion: Barry Jenkins, an independent filmmaker who had recently won the Best Picture Oscar for his film, MOONLIGHT (2016)— only the second African-American director to do so in the Academy’s long history. While his ethnicity is undoubtedly an important & inextricable element of his artistry and his worldview, it could be argued that his inclusion on Time’s list was due more to his individual significance within the media landscape. To me, Jenkins isn’t just a profoundly inspirational figure who launched himself from the microbudget realm to Oscar glory, he’s also wholly representative of ideals that the theatrical medium must adopt if it hopes to survive the 21st century. Jenkins’ cinema seems to argue for a better path, where the insatiable quest for ever-higher box office returns and the cynical catering to the lowest-common denominator is replaced by a decentralized model that favors self-expression, empathy, and community-building. Indeed, his complete lack of ego and his palpable, non-competitive passion for the work of his contemporaries shines through in his work. From his 2008 microbudget debut, MEDICINE FOR MELANCHOLY, to his recent streaming series THE UNDERGROUND RAILROAD, Jenkins’ work radiates compassion and love. To watch his work is to watch his empathy in action; we bear witness to a kind of unconditional love for his subjects not necessarily for who they are, but for who they have the potential to be.

Straddling the informal threshold that separates Generation X and the Millenials, Jenkins was born November 19, 1979 in Miami. He was the youngest of four children, none of whom shared the same father (3). His family life was anything but the nuclear ideal, with Jenkins forced to navigate a rocky relationship with a father who refused to believe the authenticity of his paternity and abandoned his mother during the pregnancy (3). He grew up in an overcrowded apartment in the neighborhood of Liberty City, raised by an older woman who had looked after his own mother as a teenager (4). At twelve, his estranged father passed away, further isolating him within the world. Despite his hardscrabble origins, Jenkins would display his bright potential quite early. While a student at Northwestern Senior High, he would demonstrate his inherent athleticism by running track and playing football (3). He also displayed an insatiable curiosity about art— specifically, cinema. He would continually raid the Foreign section of his neighborhood Blockbuster Video, gorging on French and Asian New Wave films in particular. The sight of Quentin Tarantino on a VHS cover led to his larger discovery of Wong Kar-Wai’s CHUNGKING EXPRESS (his distribution company had brought the film to the States), which Jenkins would later credit as the “inciting event” that drove his decision to pursue filmmaking as a career (1).

The path to said career began in Tallahassee, where he enrolled at Florida State University’s College Of Motion Picture Arts (4). Jenkins thrived in this new environment, feasting on foundational texts like Walter Murch’s “In The Blink Of An Eye” (1) and surrounding himself with like-minded people who would go on to become key creative partners— people like cinematographer James Laxton, producer Adele Romanski, and editors Nate Sanders and Joi McMillon (5). This period would result in the production of Jenkins’ first serious works, a pair of shorts titled MY JOSEPHINE and LITTLE BROWN BOY (2003). Both films evidence Jenkins’ talent in its rawest form, with the growing pains that accompany the discovery of his voice’s particular contours.

MY JOSEPHINE

Believe it or not, Jenkins’ career in filmmaking was almost over before it even began. At one point in his studies, he experienced a crisis of confidence so severe he took an entire year off. As he worked through his doubts about his own talent, he began to piece together the inspiration for the short he’d make upon his return (1). He was struck with amusement by his roommate’s obsession with Napoleon Bonaparte, finding himself on the receiving end of a relentless stream of arcane trivia. At the same time, he was still processing his own personal response to the world-shattering events of September 11th two years earlier; more specifically, he was interested in the fortitude of the immigrant experience in America, resilient in the face of racist hostility that now flourished out in the open under the guise of “patriotism”. Unlike the vast majority of student films that arise from a desire to emulate their makers’ favorite works, the short that Jenkins would come to call MY JOSEPHINE is the product of genuine self-expression; it is filmmaking as an act of empathy. In using the artistic process as a means to sympathize with a worldview drastically different from his own, he finds that he and his subjects are more alike than they are different— united by the universal emotions of love and heartache and the existential alienation of their “otherness”. That Jenkins considers MY JOSEPHINE one his own favorite pieces to this day speaks to his refreshing lack of ego (1).

Presented entirely in Arabic, MY JOSEPHINE would rekindle Jenkins’ faith in his artistic abilities via the embrace of his visual impulses. In other words, he doesn’t attempt to overly compose the image or find “the perfect shot”; the lyrical, expressionistic style that results is pure emotion and feeling. Shot on 16mm film, the short roughs out a simple, yet evocative sketch about an Arab-American laundry store owner (Basel Hamdan) pining for his beautiful but standoffish employee (Saba Shariat). Jenkins and cinematographer James Lanton amplify the emotionality of their subtle narrative with a high-contrast, desaturated image awash in a teal tint. They also employ a variety of camera techniques in a bid to capture the volatile interiority of the story’s protagonist: handheld camerawork and dolly movements set the stage for a continual struggle between passion and discipline, while overcranking, slippery rack-focusing, and even a spinning “tumble-dry” effect evoke the dizzying intoxication of unrequited love. Jenkins also employs an ambient orchestral score, the distorted qualities of which foreshadow the “chopped & screwed” approach of MOONLIGHT’s music.

MY JOSEPHINE derives its title from the eponymous historical figure— the great, one-sided love affair of Napoleon Bonaparte’s life, and the one thing to remain out of reach of the man who otherwise would have everything. In transposing this framework onto the figure of a middle-class business owner, Jenkins reminds us that we are the world-changing figures of our own lives, our personal stories no less worthy of the grandness we ascribe to the major names of history. However, MY JOSEPHINE achieves an even-more potent resonance in its narrative conceit of washing the American flag. In the years immediately following 9/11, laundry owners took to washing their customers’ American flags free of charge as a show of patriotism and solidarity. It shouldn’t be lost on us that, with the vast majority of these owners being minorities, these gestures of good faith and community-building were not frequently reciprocated. Jenkins’ story reinforces the honorability of our immigrants— especially American Muslims, who endured no shortage of racist mistreatment as they were lumped together with a small band of extremists who did not share their values. This idea was born of Jenkins’ observation that in the modern South, being Muslim was “the new black” (1), but it also illuminates a more-universal truth: simply by being here, our immigrants are arguably our greatest patriots… working invisibly, behind the scenes, doing the thankless, unglamorous work of spit-polishing the American Dream. That they don’t fit into the dominant white Anglo-Saxon paradigm speaks to the core of Jenkins’ artistic character, predicting the subsequent shape of his career as a tireless search for the dignity, beauty, and humanity of all people— and an insatiable desire and curiosity to tell the stories that mainstream American cinema will not.

LITTLE BROWN BOY

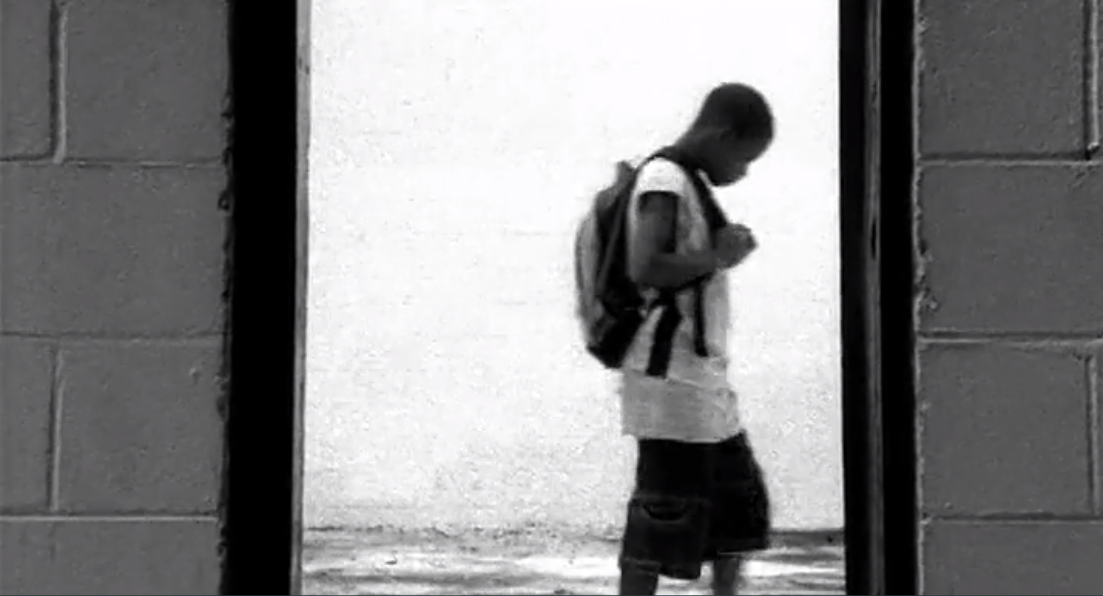

Also made in 2003, LITTLE BROWN BOY doubles down on Jenkins’ interest in stories from the edge of society. The short features DeQynn Gibson as CJ, a lonely & withdrawn boy who, given what we know about Jenkins’ own backstory, seems to share more than a few traits with his maker. He’s introduced in a rather shocking manner, witnessing a shooting during a heated argument at a basketball game and subsequently using the victim’s own handgun to dispassionately dispatch the original shooter. This episode, however, seems to be a bit of venomous fantasy— a bitter projection of anger that’s been fostered by his solitary existence. Indeed, he seems to have no friends or family to speak of, save for a distant father who can’t be bothered to come to the phone when he calls. At 8 minutes long, LITTLE BROWN BOY is more of a tone poem than a full-blown narrative, with Jenkins content to simply follow CJ around the industrial fringes of town until the young boy discovers the unexpected beauty of ruins in an overgrown field.

Jenkins’ second student short reteams the burgeoning young filmmaker with his MY JOSEPHINE collaborators, cinematographer James Laxton and production designer Joi McMillon. The resulting style is expectedly similar to their first effort, albeit rendered entirely in high-contrast black and white. The handheld camera is loose and restless, responding intuitively to action within the frame rather than imposing a particular style. Also like MY JOSEPHINE, a slippery, shallow depth of field continually searches for focus, echoing CJ’s tenuous grip on his surroundings. All this, combined with moments of CJ breaking the fourth wall to look directly into the lens, is highly reminiscent of early portions of MOONLIGHT— the short becomes, in retrospect, a proving ground for the later film’s animating ideas and unique tone, allowing Jenkins to test out a soulfully evocative style in a safe environment.

Despite his high-profile triumphs in recent years, Jenkins is quick to proclaim that he’s still as much of an amateur as he was during the time of these productions (1). What he’s really saying, though, is that he’s a perpetual student, and that seems to be the key to understanding his artistic nature. His steadfast refusal to believe his own hype has arguably made him one of the most likeable personalities in the industry. Whereas other filmmakers of his stature tend to make grand proclamations, Jenkins uses his work to pose thoughtful questions. By actively inviting us into his artistic process, his inclusive worldview becomes all the more accessible and genuine.

MY JOSEPHINE is currently available as a standard-definition stream via The Criterion Channel, while LITTLE BROWN BOY is currently available as a standard-definition stream via Fandor on Amazon Prime.

References

- Criterion Channel doc on Barry

- Via Wikipedia: Barry Jenkins: The World’s 100 Most Influential People”. Time. Retrieved September 23, 2020.

- Via Wikipedia: Stephenson, Will. “Barry Jenkins Slow-Cooks His Masterpiece”. The Fader. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

- Via Wikipedia: Rodriguez, Rene (February 27, 2017). “‘Moonlight’ director says growing up in Miami, ‘Life was heavy,’ but it’s a ‘beautiful place'”. Miami Herald. Retrieved January 18,2020.

- Via Wikipedia: Rapold, Nicolas (2016). “Interview With Barry Jenkins”. Film Comment. 52 (5): 44–45. ISSN 0015-119X.

Credits:

My Josephine:

Produced by: Jai Tiggett

Written by: Barry Jenkins

Director of Photography: James Lanton

Production Designer: Joi McMillon

Editor: Meghan Robertson

Little Brown Boy:

Written by: Barry jenkins

Produced by: Mark Ceryak and Morgan Hanner

Director of Photography: James Laxton

Production Designer: Joi McMillon

Editor: Christi Leftwich

Music by: Alex Davis