The series of collaborations between directors Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez reached their apex in 2007 with the release of GRINDHOUSE. The project was an ode to a bygone era from their youth, where cheesy genre and exploitation films where shown on a double bill in cheap art-house theatres. As the megaplex and the blockbuster rose to prominence, both the double feature and the grindhouse tradition fell to the wayside. Because this kind of cinema had so profoundly influenced the styles and careers of both Tarantino and Rodriguez, they felt compelled to keep the grindhouse tradition alive.

So plans were hatched for each director to make a feature typical of the low-budget cheese that held such a special place in their hearts, with the aim to present both films together as one big experience. Rodriguez shot a sci-fi zombie film entitled PLANET TERROR, and Tarantino paid tribute to the shrinking stunt industry with his auto slasher picture DEATH PROOF. They even went so far as to include fake trailers for other, nonexistent films shot by like-minded directors (such as Eli Roth and Rob Zombie, to name a few). Working out of Rodriguez’s Texas-based Troublemaker Studios, the two men feverishly constructed this passion project of theirs, eventually releasing the final 4-hour film to cinemas in the spring of 2007. The reward for their all that hard work and passion? Widespread disappointment and failure.

There’s a story from my own experience with GRINDHOUSE that I think perfectly sums up why the film failed. I went to the opening day screening with a college buddy of mine, and a great deal of excitement—we both knew what to expect and were looking forward to 4 hours of trashy fun. A small crew of bros sat in the row ahead of us, no doubt buzzing with anticipation for the jeager bombs they’d slam later that night. An usher stood up in front of the audience and announced that the film we were about to watch ran for almost four hours. The bros in front of us, who had obviously not done their homework, immediately balked. “Fuck that bro, let’s go watch TMNT instead!” I’m not joking—they literally said those exact words.

Naturally, my buddy and I found this and their subsequent march out of the auditorium hysterical, but in retrospect I can’t help but wonder if this was going on in every theatre across America. Audiences today are different than they were during grindhouse’s heyday. Their attention span literally can’t handle the idea of a four film, regardless of who made it or how good it might be. In many ways, GRINDHOUSE was doomed to failure before the directors even began writing it.

Personally, I loved GRINDHOUSE. I found each entry to be tremendously entertaining, especially the fake trailers that played between the features (Eli Roth’s THANKSGIVING trailer is easily superior to anything else he’s ever done). DEATH PROOF, Tarantino’s entry, is the better film on almost every level, and while it could be counted as the director’s first high-profile failure, it is also something of a triumph on many levels.

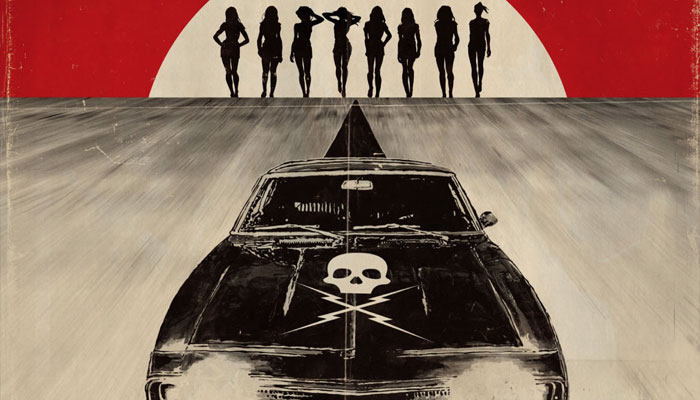

DEATH PROOF is the hokey slasher film that John Carpenter never made. It concerns a salty character named Stuntman Mike (Kurt Russell), who drives around in a jet-black hot rod that’s been outfitted to sustain the driver’s life in the event of a horrible collision. Initially designed to allow stuntmen to walk away without a scratch after performing their daredevil feats, Stuntman Mike now uses this car to stalk and kill hapless young women.

The story is divided into two acts. In the first, a group of girls, led by a sassy, Amazon queen and radio host named Jungle Julia (Sydney Tamiia Poitier), are en route to a lakeside cabin vacation for the weekend. They stop off at a local Austin dive for some drinks, where they meet and ultimately fall victim to Stuntman Mike. In the second half, Stuntman Mike has relocated to rural Tennessee and stalks a group of young girls on leave from a film shoot, only to find that they’re just crazy enough to play his own game against him.

DEATH PROOF exists in two versions: a two hour director’s cut that screened at Cannes as well as on its own during a European theatrical release, and a heavily-streamlined cut that was included in the American GRINDHOUSE theatrical release. Mostly available now in its longer form on home video, DEATH PROOF can be a bloated film prone to long stretches of dialogue that subverts the very nature of the type of film its trying to be. Thankfully, Tarantino’s cast is so charming that you don’t mind these long stretches.

Kurt Russell is perfect as the deceptively disarming Stuntman Mike. Firmly ensconced in middle age, Russell is in the perfect window to benefit from the Tarantino Effect, and like John Travolta or Robert Foster before him, he saw his celebrity rise in the wake of his devious performance. Russell doesn’t act much these days, but DEATH PROOF became a cause to look at his career in a different light, one that afforded more respect and recognition of his contribution to the art form. Russell’s psychopathic cowboy demeanor is captivating, making for one of the most fully-realized movie monsters in recent history. I could watch him play the role all day. Hell, he’s a psychotic murder and I want to be friends with him!

In the first half, Sydney Tamaiia Poitier (yes, as in the daughter of that Sydney Poitier) leads the story as the sultry Jungle Julia. She’s a Tarantino creation through and through, with a firm command of obscure pop culture to match her large vocabulary. To help her get into character, Tarantino reportedly told Poitier that Jungle Julia is to music as what Tarantino is to film.

Relative unknown Vanessa Ferlito scorches up the screen as Roxanna, a no-nonsense Brooklynite who is cajoled into giving Stuntman Mike a lapdance (one of DEATH PROOF’s centerpiece sequences).

Rose McGowan, who headlined PLANET TERROR for Rodriguez, appears in a small role as Pam, a bubbly, ditzy platinum blonde bimbo that finds herself the unwitting occupant of the one seat in Stuntman Mike’s car that isn’t death-proof. Fellow director Eli Roth–whose breakout film HOSTEL (2005) was produced by Tarantino–plays Dov, an aggressive frat dude hellbent on getting laid. Omar Doom plays Dov’s Jershey-Shore-styled buddy, who pursues girls in an effete, whiny manner that suggests heterosexual sex may not really be his bag. And finally, Tarantino himself appears as Warren, the dive bar owner who’s getting just a bit too old to be partying alongside his young customers. Like his performance in 1995’s FOUR ROOMS, he mentions a particular drink being a “tasty beverage”, yet another reference to the endlessly-quotable lines he’s concocted for his fictional characters throughout his work.

The second half is comprised of an even livelier cast than the first. This group of girls is arguably the most archetypically Tarantino-esque that he’s ever created. They all work in various positions in the film industry as actresses, makeup, and stuntwomen. This means that they’re all incredibly well-versed in pop culture and can act as Tarantino’s mouthpieces through which to reference obscure cult films. Rosario Dawson plays Abernathy, the sassy, sensible member of the group. Mary Elizabeth Winstead plays Lee, the dainty, feminine actress in a cheerleader outfit. Tracie Thoms comes off as the female Samuel L. Jackson in her performance as feisty stunt-driver Kim. And finally, Kiwi revelation Zoe Bell, who performed as Uma Thurman’s stuntwoman in the KILL BILL saga, plays a leading role as a fictionalized version of herself. For a stuntwoman, she has a remarkably charismatic screen presence that allows the audience a window into the story. She just seems like a person who’s endless fun to be around, and her unmitigated zeal for life and adrenaline is infectious.

Rounding out the supporting cast are a few familiar faces. Veteran character actor Michael Parks reprises the Earl McGraw/cowboy sheriff role he originated in Rodriguez’s FROM DUSK TILL DAWN (1996) and continued on through KILL BILL VOLUME 1 (2003), each performance more exaggerated than the last. Jonathan Loughran, a member of Adam Sandler’s repertory of performers, plays a redneck mechanic played Jasper. Nicky Katt, who has been well-utilized by such directors as Christopher Nolan and David Gordon Green, has a small cameo as a shady convenience store clerk who hawks European versions of Vogue Magazine under the table like they’re narcotics.

Because he’s working away from his home base in California and setting up shop in Rodriguez’s Texas studios, Tarantino doesn’t have the luxury of working with most of his regular collaborators this time around. Sure, he’s got editor Sally Menke and the Weinstein brothers as his producing partners, but he’s firmly in Rodriguez’s territory. For the first time in his career, Tarantino takes a stab at being the Director of Photography, which works out pretty damn well. Having taken a film class or two, I know firsthand how difficult it is to light for, expose, and shoot actual celluloid film. Despite never receiving a formal education in this arena, Tarantino pulls off the feat effortlessly. It also probably helps that the film is supposed to look junky and battered.

Shot in the 2.35:1 aspect ratio, Tarantino cultivates a look that’s very much like they shot using the cheapest film stock around. The colors are burnt-out, with a strong magenta cast that suggests the fading that comes from storing film in improper conditions. The image is littered with scratches and frame drops that give the appearance of a film that’s been beaten up and dragged across rough terrain– which is what Tarantino and company physically did to achieve this look (no digital trickery was used!). Menke–one of the greatest editors to have ever lived–does a great job emulating an amateur hack job with dropped frames, jumpy edits, and repeated takes. Strangely enough, both Menke and Tarantino are fully committed to this stylistic conceit during the first half, only to all but abandon it for a cleaner, clearer approach in the second half.

In terms of the cinematography, Tarantino lenses the film in a way that stays consistent with his earlier work. When shooting close-ups, he tends to show his characters in profile instead of the standard over-the-shoulder composition. In the first half’s dive bar sequences, he uses high-key, expressionistic lighting and copious amounts of neon to create a lurid, foreboding look that also evokes the surrounding Texan desert.

In the beginning of the second half, Tarantino chooses to show the convenience store sequence almost entirely in black and white, like he did for the House of Blue Leaves massacre in KILL BILL VOLUME 1. Why he does this, I’m not entirely sure. It seems to be a pure style indulgence on Tarantino’s part, as it doesn’t call attention to itself as a grindhouse-specific homage.

Tarantino’s camerawork is solid and unencumbered, moving with deliberate purpose. He uses tracking shots and circular dolly shots to decent effect, which is appropriate considering the grindhouse films he is evoking weren’t necessarily known for their virtuoso camerawork. His restraint pays off when the film abruptly changes gears and becomes a breathless car chase. The undeniable highlight of the film, this sequence contains some of the imaginative chase coverage put to film, thanks to Tarantino’s surprisingly confident eye for action. When a list of Tarantino’s best film moments are eventually compiled, the driving sequences of DEATH PROOF will easily rank within the top five, if not higher.

Tarantino’s eclectic mix of pre-recorded music for DEATH PROOF stands out as one of the best amongst his entire filmography. He’s compiled a truly inspired mix of southern rock, soul, surf rock, and other sounds that bolster and complement the grindhouse aesthetic. The two most notable tracks are The Coasters’ border town booty-shaker “Down In Mexico”, as well as a hyper, slasher-movie appropriate theme song by April March called “Chick Habit”. Once again, Tarantino rescues a handful of excellent songs from obscurity and pairs them with the visuals in such a way that one can never be disassociated from the other ever again. Just try listening to Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick & Tich’s “Hold Tight” again without thinking of a dismembered leg flopping onto the highway:

Tarantino has gone on record stating that he personally believes DEATH PROOF to be his worst film. This is most likely because it is by far his most indulgent film, where all his signature techniques and tropes are cranked up to eleven. What can you expect from a film directed by a noted foot fetishist when the opening credits play against a women’s foot in close-up? The extreme gore, the yellow-colored title font, abrupt non-diagetic music stops, seemingly-interminable sequences of clever dialogue and profanity combinations, the trunk shot (this time from the hood’s POV) Kurt Russell breaking the fourth wall by smirking directly at the audience—all the Tarantino tropes are here in some form. By now, the components of Tarantino’s self-contained universe are well-established amongst his followers, so he treats DEATH PROOF as one big in-joke. Characters mention Big Kahuna burger, order Red Apple cigarettes (both Tarantino-created brands), one character has the Twisted Nerve song that Daryl Hannah whistles in KILL BILL VOLUME 1 as her cell ringtone, the action takes near his birthplace in Tennessee, and (in a well-hidden nod to the fake trailer he directed), Eli Roth toasts to Thanksgiving before pounding a shot of Wild Turkey. Tarantino fans will undoubtedly enjoy discovering each hidden reference, but for the casual viewer, this all might fly right over their heads.

DEATH PROOF may be Tarantino’s weakest feature, but it is still a recklessly entertaining ride that I wouldn’t hesitate to revisit. Its vintage charms make for one of the most bracingly original films in years, despite the fact that it’s essentially a pastiche of exploitation film conventions. DEATH PROOF marks a stylistic saturation point, the end of Tarantino’s Tex-Mex phase and his last (so far) collaboration with Rodriguez. Whether the failure of DEATH PROOF and the complete dismantling of their original distribution plan for GRINDHOUSE caused him to back away from this direction is open to debate, but I’d suggest it’s likely. For a lot of directors, creating an overly-indulgent film can have career-wrecking consequences, but by getting it all out of his system in DEATH PROOF, Tarantino is able to clear the way for new ideas and concepts that will elevate him even further into the pantheon of great directors.

DEATH PROOF is currently available in high definition Blu Ray in its extended Director’s Cut, or its double-feature GRINDHOUSE incarnation from Genius Products.

Credits:

Produced by: Elizabeth Avellan, Robert Rodriguez, Erica Steinberg, Bob Weinstein, Harvey Weinstein

Written by: Quentin Tarantino

Director of Photography: Quentin Tarantino

Production Designer: Steve Joyner

Edited by: Sally Menke