In my 2012 essay for SUNCHASER, director Michael Cimino’s 1996 feature film, I wrote that the notoriously reclusive and mercurial filmmaker probably had one or two great films left in him, but I also concluded that he probably wouldn’t seize the opportunity. It saddens me to know that I was right– Cimino died of unknown causes on July 2nd, 2016, at the age of 77. His body was discovered lying in his bed at his home in Beverly Hills, after friends had not been able to reach him for several days (1). This left the poorly-received SUNCHASER as his final feature effort, and a short contribution to 2007’s TO EACH HIS OWN CINEMA project, “NO TRANSLATION NEEDED” as his final completed work overall. Throughout the operatic sweep of Cimino’s career from prodigy to pariah, critics and fans alike chose to believe in his innate talent, wishing for one final masterpiece that would redeem his ruinous career and restore his standing amongst the pantheon of great American directors. Now, we know for certain that final masterpiece will never come; leaving Cimino’s legacy to the Icaresque fall from grace that was often invoked in numerous essays and think-pieces– the ultimate cautionary tale.

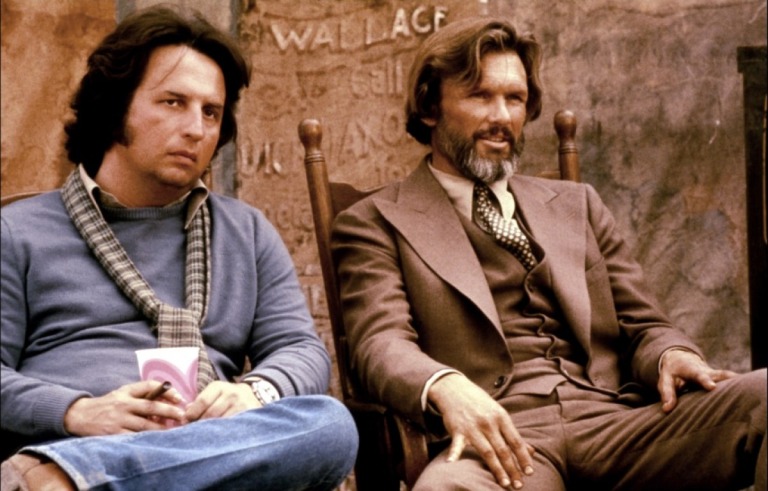

Cimino’s career– indeed his entire life– was nothing less than the glory and the ruin of the American Dream, seemingly cut from the same operatic cloth as his cinematic epics. Born in 1939 in New York City, the young Cimino was regarded as something of a student prodigy, but he also earned an equally-notorious reputation as a troublemaker and a schoolyard brawler. His intellect and natural curiosity about the world enabled his admission to Yale, where he studied painting, architecture, and art history. His love for the films of John Ford, Luchino Visconti, and Akira Kurosawa enabled his postgraduate rise as a highly sought-after director of commercials in New York during the 60’s. Some of his best known work from this period, including spots for United Airlines and Pepsi, established several of his signature traits as an artist, such as elaborate set design and the iconography of Americana. It was also during this period that Cimino met perhaps the most influential figure in his life: on-again/off-again producing (and life) partner, Joan Carelli (2). Carelli was actually the one who encouraged Cimino to jump into writing for feature films– she sensed a potential in him that was almost immediately realized when he moved to Los Angeles in the 1970’s and began writing scripts for actor/director Clint Eastwood. Eastwood was so impressed with Cimino’s work on a little heist script called THUNDERBOLT & LIGHTFOOT that he offered up his directing chair to the budding filmmaker. The surprise success of that film emboldened Cimino to swing for the fences with his next film– 1978’s THE DEER HUNTER. This film saw the synchronization of Cimino’s ambition with his talent, generating a staggering, once-in-a-lifetime master work that dominated the Oscars and catapulted him into an nearly-unparalleled echelon of prestige. The runaway success of THE DEER HUNTER made it quickly apparent to everyone that Cimino had fulfilled his initial promise as a bonafide prodigy.

Unfortunately, Cimino would never reach these lofty heights again. His reign at the top would end just as quickly as it had begun. Up until this point, Cimino’s ego and confidence had worked in his favor– THE DEER HUNTER is undoubtedly the product of a self-assured director who knows how to mold his vision in the shape of Greatness. However, there’s a fine line between vision and megalomania. Given full creative control and a virtually unlimited budget, Cimino capitalized on his success to make HEAVEN’S GATE— a sweeping, epic Western that he envisioned as a serious contender for the mantle of “Greatest Film Of All Time”. Anything– the cast, the sets, time, money, virtually everything— was disposable in service to achieving his ambitious vision. He gained a reputation as something of a tyrant– or a fascist– on set, leading to crew members calling him “The Ayatollah” behind his back. Despite numerous budget and schedule overruns, Cimino eventually finished HEAVEN’S GATE, but the damage had already been done. In his persistence to craft the Perfect Story, he had lost control of his own narrative– months of damning set reports in the press led to the film accumulating the stink of failure before it was even released, and audiences followed suit. The financial loss of HEAVEN’S GATE was so great that it almost single-handedly bankrupted its studio, United Artists, and essentially closed the door on the New Hollywood era of director-driven films.

That Cimino’s own career was thrown into ruin amidst all this devastation is something of afterthought. Claims that he was a one-sided and factually-inaccurate storyteller positioned him as a politically-incorrect relic on the fringes of an increasingly-PC culture. He languished in this state of exile for the next 5 years, suffering no shortage of aborted attempts to mount another film. The making of 1985’s YEAR OF THE DRAGON offered a chance for Cimino to redeem himself with a lean, pulpy crime thriller, and his genuine attempts made for a modest success; a beacon of hope. However, he would not make the most of his second chance. His next effort– 1987’s THE SICILIAN— fell prey to his ego-driven indulgences, despite compelling subject matter and a deeply personal connection to Cimino’s heritage as an Italian American laying the foundation for what could have been a great film. THE SICILIAN’s failure signaled the beginning of Cimino’s permanent downturn as a filmmaker. 1990’s DESPERATE HOURS claimed the dubious distinction as his last film to be released theatrically, its failure kicking off another period of extended exile. When Cimino finally returned with SUNCHASER in 1996, he had been an irrelevant filmmaking force for nearly two decades. Despite receiving a prestigious screening slot at Cannes, the film would ultimately go straight to video. A mismatched buddy / road film like THUNDERBOLT & LIGHTFOOT, SUNCHASER found Cimino working from a burst of newfound inspiration that suggested he might still yet find redemption. It could’ve been that SUNCHASER came somewhat full circle with the beginning of his career, or that he was shooting in the same dramatic landscapes as the classic John Ford westerns that captivated his imagination in his youth, but Cimino’s final feature seemed to be in possession of a palpable energy that had otherwise been missing.

The director’s final years saw some flashes of creativity– aside from his short film for Cannes’ TO EACH HIS OWN CINEMA project, he became a novelist in 2001 with the publication of his book, “Big Jane”, which he followed up in 2003 with another book titled “Conversations En Miroir”– but his work was overshadowed by furtive rumors and gossip. Because he rarely gave interviews, he become regarded as a reclusive eccentric, and a drastic, almost-overnight change in his facial features generated hushed whispers all over town that he had butchered himself with plastic surgery, or that he was undergoing a sex change operation. Of course, Cimino didn’t try too hard to dispel these rumors himself– he was notorious for giving contradictory information about his personal life in what could be construed as a bid to inject an air of mystique around his celebrity.

For all his faults as a storyteller, Cimino’s visual aesthetic drew a consistent crowd of admirers. Fundamentally inspired by Ford’s Monument Valley westerns, he utilized America’s striking vistas and landscapes to his own benefit, giving his work a dramatic Cinemascope backdrop that infused his stories with the potent aura of myth and folklore. His scholastic background in architecture and art history fueled an impeccable intuition for composition, but it also informed his sense of narrative structure– for instance, the organization of THE DEER HUNTER’s three distinct acts recalls the conventions of triptych. His camerawork favored the classical techniques of old-fashioned studio epics, often rendering his elaborate sets and bustling locations in sweeping, romantic crane or dolly moves. This majestically-minded aesthetic reached its apex with HEAVEN’S GATE, where Cimino’s insistence on an immersive environment led to his crew effectively building out an entire town for him to swoop and soar through. The catastrophic failure of HEAVEN’S GATE would impact his style with a palpable loss of confidence in YEAR OF THE DRAGON and onward, but his aspiration for visual grandeur would remain.

Critics might have derided Cimino as a tyrannical fascist, but the fact remains: the success of his artistic vision depended on the strength of his collaborators. Throughout his career, he developed a rather eclectic group of collaborators on both sides of the camera. His most influential collaborator was Carelli– although she only officially served as a producer on HEAVEN’S GATE and THE SICILIAN, she was instrumental in putting Cimino on the road towards filmmaking in the first place, and she remained a close friend and confidant for the rest of his life. Composer David Mansfield boasted the highest quantity of partnerships with Cimino, having shaped the distinct musical character of HEAVEN’S GATE, YEAR OF THE DRAGON, THE SICILIAN, and DESPERATE HOURS. Mickey Rourke was the closest thing Cimino had to his own DeNiro, headlining YEAR OF THE DRAGON and DESPERATE HOURS after his slight cameo in HEAVEN’S GATE. Jeff Bridges and Christopher Walken also put in two tours of duty eac, appearing separately in Cimino’s first two features before sharing the bill on HEAVEN’S GATE. Whereas most visually-esteemed directors owe a debt of gratitude to their partnership with a singular cinematographer, Cimino cultivated fruitful relationships with no less than three. The venerated DP Vilmos Zsigmond is responsible for Cimino’s visual hallmarks: THE DEER HUNTER & HEAVEN’S GATE. Alex Thompson replaced Zsigmond on YEAR OF THE DRAGON and THE SICILIAN– two films that were admired for their visuals if not for their storytelling. Douglas Milsome saw Cimino through to the end of his filmography, countering the bland beige environs of DESPERATE HOURS with the vibrant vistas of THE SUNCHASER.

As a third generation Italian American, Cimino was deeply fascinated with the immigrant experience in America– a conceit that gives his filmography a unique bent that’s at once both patriotic and deeply critical of his homeland (some would argue that to be deeply critical is to be patriotic). Films like THE DEER HUNTER and HEAVEN’S GATE explored the unique contributions that Eastern Europeans have made to American history, while YEAR OF THE DRAGON portrays the Chinese-American perspective as deeply-tied to the heritage of the country’s railroad system. His only film to not take place in America– THE SICILIAN— still manages to work its way into this conceit with its narrative drive to establish an American state in Sicily. A deep nostalgia runs through Cimino’s filmography; a subliminal undercurrent of loss and mourning for an era long gone. Especially within his first three films, his characters are relics trapped in a world that no longer has any use for them. Again, HEAVEN’S GATE is a prime example of this conceit in action: it’s a story about the closing of the frontier; the end of the Wild West. The arrival of the railroad brings with it an influx of civilization, and the homesteaders valiantly struggle to maintain their way of life in the face of great upheaval and change. The iconography of Americana that peppers Cimino’s films belies a conservatively-minded patriotism that sees the past through rose-tinted glasses. Indeed, I suspect that Cimino just might have been a fan of Donald Trump’s campaign to “Make America Great Again”.

Cimino’s artistic voice was distinctly masculine– his films exclusively featured male protagonists, but this wasn’t necessarily a product of sexism or even simply a disinterest in female-oriented narratives. He was genuinely interested in exploring the peculiar dynamics of platonic male-to-male relationships. His protagonists often possessed shades of complexity underneath their surface machismo, and their individual inner journeys often coincided with masculine ideals and virtues. THUNDERBOLT & LIGHTFOOT is framed as a buddy comedy, but the film resonates as a tender portrait of brotherly bonds, giving new meaning to the phrase “thick as thieves”. THE DEER HUNTER explored the idea of male friendship as fractured by profound loss, filtered through the prisms of loyalty, responsibility and patriotism. HEAVEN’S GATE mostly portrays antagonistic male relationships, illustrating how actions and reactions are codified by a common sense of honor and natural law. THE SICILIAN further tackles these conceits while complicating them via a loose father/son relationship between hero and villain. DESPERATE HOURS is fundamentally concerned with patriarchal dynamics, using the template of the home invasion thriller to examine the distinct responsibility a man has to his family as both the breadwinner and the protector.

Religion, ritual, and spirituality is yet another common theme uniting Cimino’s disparate works. The Italian immigrant experience in America is fundamentally informed by its rich heritage with the Roman Catholic faith, and like his generational peer Martin Scorsese, Cimino shows great interest in how spirituality guides human interaction. Whereas Scorsese’s work tends to grapple with the inherent conflict of religious belief, Cimino’s cinematic interpretations of faith are explored through ritual and ceremony. THE DEER HUNTER is the most obvious example; beginning with a wedding and ending with a funeral, the cycle of life portrayed in the film is one marked by distinct milestones and sacraments. Despite being a meditation on the law of man as informed by the wilderness, HEAVEN’S GATE riffs on the ceremonial nature of this signature by positioning the town skating rink as a de facto community center, town hall, and cathedral. YEAR OF THE DRAGON compared and contrasted western religious tenets with those of the Far East in a bid to find the common ground that dictates their interactions. THE SICILIAN is perhaps Cimino’s most direct reckoning with Christianity, heavily dealing in Old World dogma and its history of religious persecution. In THUNDERBOLT & LIGHTFOOT and SUNCHASER especially, Cimino also shows a deep interest in an elemental, indigenous spirituality that is more connected with nature and the landscape than the religious constructs of civilization. The protagonists in those films are able to tap into the energy of the world around them and harness that power for their own benefit. Cimino is at his most poetic in these scenes– the final shot of SUNCHASER, showing a dying man racing to the magical lake that will purportedly save his life and instantly disappearing save for his splashing footsteps on the water, is a sublimely ambiguous conclusion that tips its hat towards the mysterious forces of nature.

The list of Cimino’s unrealized projects suggests the same sense of grandeur as his completed work. At the height of his career, Cimino dreamed of adapting Ayn Rand’s THE FOUNTAINHEAD, even going so far as to develop a screenplay after the success of THUNDERBOLT & LIGHTFOOT (3). During this period, he also worked towards realizing biopics on Janis Joplin and the infamous mafia boss, Frank Costello (4). After the catastrophic reception of HEAVEN’S GATE, Cimino tried to resurrect his career by getting himself hired on films like THE POPE OF GREENWICH VILLAGE and FOOTLOOSE, only to then get himself fired when his egotistical pursuits got the best of him. Still other unmade films include a biopic on 1920’s Irish rebel Michael Collins and SANTA ANA WINDS (5), which would have been a contemporary romantic drama set in Los Angeles (6). It’s clear that Cimino did not intend for SUNCHASER to be his final film– as late as 2001, he was in China scouting locations for a planned 3-hour epic about the origins of the Chinese Revolution called MAN’S FATE (7). An abandoned or aborted film in any filmmaker’s career is a small tragedy, but in the case of a career like Cimino’s, which brilliantly flamed out almost as soon as it had begun, any chance he had at restoring his luster was one he could not afford to squander. Unfortunately, it appears he did on several occasions.

Whatever the final word on his legacy may be, his Oscars and Film Registry induction for THE DEER HUNTER cannot be taken away. They can be reconsidered from a critical standpoint, sure, but they cannot be physically recalled. Those achievements alone make Cimino an important figure in the cinematic landscape, and the dizzying highs and nauseating lows of his career further merit careful study from film historians and students alike. Ego is an extremely powerful tool in any master director’s toolbox, but it also a dangerous vice that must be monitored and kept in check. Cimino indulged his ego too much, to the point that his sense of personal infallibility severed his connection to the emotional truths he needed to convey. While his director’s cut of HEAVEN’S GATE has re-emerged as a lost classic on par with earlier work like THE DEER HUNTER, it nevertheless clearly marks the point where he began buying into his own hype, beginning a long tailspin from which he would never recover. For all his strengths, vision, and promise as a filmmaker, he ultimately failed because he repeatedly abandoned the narrative at hand to tell the story he found more interesting: himself.

Ironically enough, many critics suggest that a biopic on Cimino’s own life and career would itself make a great film.

References:

- Via Wikipedia: “‘Deer Hunter,’ ‘Heaven’s Gate’ director Michael Cimino dies”.The Washington Post Online. The Washington Post. Retrieved July 3,2016.

- Via WIkipedia: Griffin, Nancy (February 10, 2002). “Last Typhoon Cimino Is Back”. The New York Observer 16 (6): pp. 1+15+17. Retrieved August 27, 2010.

- Via Wikipedia: Chevrie, Marc; Narboni, Jean; Ostria, Vincent (November 1985). “The Right Place” (in French).Cahiers du cinéma (n377).

- Via Wikipedia: “MICHAEL CIMINO, CANARDEUR ENCHAINÉ / réalisateur de Voyage au bout de l’enfer, La Porte du Paradis, L’Année du Dragon …” (in French). michaelcimino.fr. Retrieved May 4, 2011.

- Via Wikipedia: Klady, Leonard (October 4, 1987). “Checking On Cimino”.Los Angeles. Retrieved May 29, 2011.

- Via Wikipedia: Cieply, Michael (January 26, 1988). “Firm Cancels New Cimino Film Project”. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 30, 2011.

- Via Wikipedia: Macnab, Geoffrey (December 6, 2001). “War stories”. The Guardian. Retrieved April 30, 2011.