After achieving success with his boundary-pushing sex comedy IRMA LA DOUCE (1963), director Billy Wilder and his writing partner I.A.L. Diamond attempted to strike gold once again by adapting another provocative play into a feature film. Their new effort was based on a play by Anna Bonacci titled “The Dazzling Hour”, but Wilder’s misanthropic sense of humor led him towards a different, more acerbic title: KISS ME, STUPID (1964). Unfortunately, the old adage that “lightning never strikes the same spot twice” proved true in the film’s case, as many felt Wilder’s taste for envelope-pushing humor went a little too far this time.

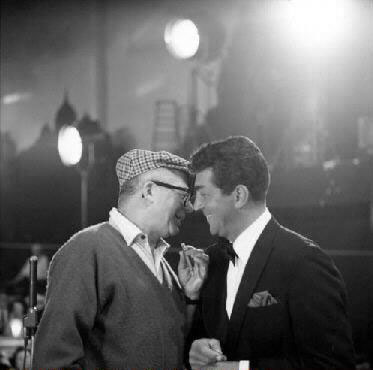

Producing in conjunction with Diamond and his longtime collaborator Doane Harrison, Wilder used the desert community of Twentynine Palms, California to stand in for a fictional Nevada town called Climax (the first of many innuendo-laden gags). The town is so small it seems comprised almost entirely of a single intersection– it’s a place where nothing exciting ever has, or ever will, happen. Or so the townspeople think, until the world-famous Rat-Pack singer Dino (Dean Martin) rolls into town on his way out of Vegas. Martin is essentially playing his smooth, dapper self here, albeit with a cartoonishly-exaggerated sexual appetite and a casual disregard for the boundaries of matrimony. This presents a major problem for local piano teacher and aspiring songwriter Orville (Ray Walston), whose marriage to the prettiest girl in the town has driven him into a perpetual state of jealousy and paranoia. Not unlike his director, Walston plays the wiry beta-male as a stickler for the integrity of the written note, and his debilitating possessiveness towards his wife, Zelda, positions him as a classical Wilder protagonist– an otherwise-decent man with a narcissistic fatal flaw that will be his undoing. Wilder initially wished to have his two-time collaborator Jack Lemmon play Orville, only to have the role temporarily filled by iconic screen comedian Peter Sellers until a sudden heart attack forced him to withdraw and Wilder to reshoot several weeks worth of scenes. Walston ultimately fills the role, delivering a capable performance as a mild-mannered husband pushed to his breaking point.

Sensing a chance to finally hit the big time, Orville and his songwriting partner Barney (Cliff Osmond) secretly sabotage Dino’s car so that he’s stuck in town for the night, and then offer to put him up at Orville’s house so they can aggressively sell him their catalog of unpublished songs. Knowing his affection for dames– especially of the married variety– Orville and Barney concoct a convoluted scheme that will get Zelda (Felicia Farr) out of the house for the night (and on their anniversary, no less), while they bring in a good-time girl from the local brothel to pose as Orville’s wife and offer up to Dino on a silver platter. Towards that end, they find Polly The Pistol– a street-smart prostitute played to trashy perfection by Kim Novak– and manage to rope her into the operation, only to discover that she can’t stand their guest and won’t be bought so easily.

Cinematographer Joseph LaShelle returns for his second consecutive collaboration with Wilder, lensing KISS ME, STUPID’s 35mm film frame in black-and-white Cinemascope. The film’s cinematography is highly consistent with Wilder’s established utilitarian aesthetic, which favors the polished sculpting of studio lighting and deep focal lengths. As in his previous work, the film finds Wilder opting to shoot wide masters and use careful framing or classical camerawork instead of cutting to complementary setups or reverse angles. His general approach suggests a belief that visual flash, or even the simple act of a cut, served to distract the audience from the performances and his carefully-crafted dialogue. If a particular scene could be adequately captured in one setup, he’d do it– case in point: a scene featuring people watching television through a store window, reflected in the glass so as to eliminate the need to cut back and forth between the broadcast and their reactions. KISS ME, STUPID’s compositions and camerawork are largely unobtrusive in this way, except for one very curious exception. In the film’s penultimate shot, Wilder sends the camera pushing in at warp speed on Farr’s face as she delivers the titular line. The line itself is evocative of Shirley MacLaine’s final “shut up and deal” line that closes THE APARTMENT, yet unlike the static camera that captured it, Wilder’s camerawork here foreshadows the transgressive, jarring techniques pioneered by the successive generation of filmmakers that included the likes of Martin Scorsese. LaShelle’s return as cinematographer is further echoed by the return of Wilder’s dependable stable of collaborators: production designer Alexandre Trauner, editor Daniel Mandell, and composer Andre Previn, who complements his conventional big band score with sourced swing and rock tracks that reflect the encroaching influence of American youth culture on mass media.

The 1960’s were a great decade for Wilder artistically, in that the cultural climate was more receptive to overt depictions of sexuality. He had helped to open this clearing himself, with the widespread success of 1959’s SOME LIKE IT HOT essentially humiliating the Hays Motion Picture Code into irrelevancy. Each of his features in the years since had become increasingly sexualized, culminating in IRMA LA DOUCE daring to position a French prostitute as the love interest to the chief protagonist. KISS ME, STUPID’s winking double entendres in particular foreshadow the rise of swinging and other liberated sexual attitudes amongst married couples in that era. For instance, Zelda barely even flinches at Orville’s (fake) confession of his infidelity– she reacts in a non-judgmental fashion that’s almost playful in its dismissiveness, as if the idea of adultery was an mundane and expected as picking up the drycleaning. There’s also the thought that Orville would offer up his own wife to Dino’s sexual carpetbombing campaign in exchange for finally making his dreams come true, a notion that Orville can only stomach because it’s not actually his wife. As in real life, both the men and women of KISS ME, STUPID use sex to get what they want, only they don’t quite know how to wield this mysterious and powerful new weapon.

To his credit, Wilder doesn’t pull any punches as to the virtuousness of his characters– he lays bare their lack of moral scruples for all to see (in the hopes that we might recognize ourselves in them). Like so many of Wilder’s past protagonists, Orville and Barney’s desperation is directly linked to their lack of success in their chosen profession, leading them to commit questionable acts in the name of their careers. This isn’t to say that Dino’s success as a singer has made him a paragon of human decency; rather, his assured identification as a rich performer gives him a guiding set of values that he can choose to act upon… even if the values themselves are not objectively positive. Indeed, the story of KISS ME, STUPID is a struggle between two sets of class values: small-town America and big-city Hollywood. Orville’s cultural paradigm is profoundly shaped by his middle-class upbringing in a rural locale– he sees women as an object to be kept. Conversely, Dino’s membership among the moneyed jet set no doubt influences his view of women as objects to be passed around. Neither value set acknowledges the woman’s agency as a person in her own right– a fact that makes it painfully obvious that sexual politics still had a long way to go.

Uniforms are another key component of Wilder’s artistic aesthetic, and while the domestic setting of KISS ME, STUPID doesn’t necessarily provide many opportunities for their inclusion, he still manages to further explore the cultural significance of their usage. The imagery of showgirls dressed in matching outfits is a literal example, but Wilder also uses Novak’s disguising of herself in the garb of a modest housewife to illustrate his conceit that costumes are themselves a form of uniform in that they signify function rather than identity.

KISS ME, STUPID further reinforces Wilder’s ties to the Rat Pack generation of celebrity, an association that goes back to his collaboration with Bing Crosby in THE EMPEROR WALTZ (1948). Beyond that, it does little to show Wilder’s growth as a filmmaker aside from his eagerness to explore the boundaries of what constitutes acceptable subject matter. Whereas his previous pioneering efforts were met with applause, the critical reception to KISS ME, STUPID was rather tepid. The film was condemned by the Catholic Legion of Decency, although that was to be expected– what Wilder really sought was the approval of the common man, and the collective pushback from that particular demographic was the blow that truly hurt. He had made his career by walking that fine line between crass and class, but many felt that his efforts in KISS ME, STUPID had finally congealed into smut. Unlike so many of Wilder’s other works, KISS ME, STUPID doesn’t seem to have grown in esteem or appreciation in the intervening decades; there’s a particularly stale air to the film’s sexual politics, a charmlessness that threatens to sink the whole endeavor if it weren’t for the few glimmering flashes of Wilder’s signature brilliance. While the seeds of Wilder’s decline were arguably sown earlier, KISS ME, STUPID makes it evident that this seeds were beginning to bear their sour fruit, and that the legendary director was firmly on the downslope of the cultural zeitgeist.

KISS ME, STUPID is currently available on high definition Blu Ray via Olive Films.

Credits:

Written by: Billy Wilder, I.A.L. Diamond

Produced by: Billy Wilder, Doane Harrison, I.A.L. Diamond

Director of Photography: Joseph LaShelle

Production Designer: Alexandre Trauner

Edited by: Daniel Mandell

Music by: Andre Previn