Ever since the disaster of 1980’s HEAVEN’S GATE, director Michael Cimino had been in a career tailspin from which he could not recover. Each successive, new project (themselves many years apart from each other) were met with an increasing chorus of negativity and a diminishing box office take. Despite his best efforts, an increasingly vain self-image and eccentric vision continued to betray him. His sixth feature, 1990’s DESPERATE HOURS, could’ve been a bid to reclaim his former glory with a gritty, contained thriller. Unfortunately, it was met with a profound indifference, signaling the dying throes of Cimino’s relevance. As of this writing, DESPERATE HOURS was the last film of Cimino’s to ever be released in cinemas.

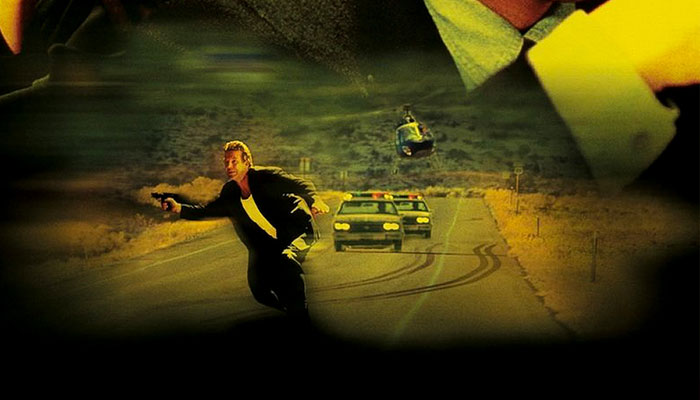

A remake of the 1955 film (and hit Broadway play) of the same name, DESPERATE HOURS features Mickey Rourke as Michael Bosworth, a charismatic criminal that stages a shockingly simple jailbreak and takes over an elegant, comfortable house in the suburbs as his hideout. While they wait for Bosworth’s lawyer-turned-lover to spirit them away to freedom, Bosworth and his posse hold the house’s inhabitants– the fractured Cornell family– hostage and subjects them to several days’ worth of psychological trauma.

DESPERATE HOURS marks Rourke’s third collaboration with Cimino, and it’s not a good sign when he’s one of the most watchable things about the movie. He paints Bosworth as a civilized psychopath; a whip smart man with thuggish instincts and a dime-turn ferocity. He calmly commands his hostages to do his bidding in a manner that’s so respectful it’s unnerving. While it’s an original characterization, Rourke ultimately can’t transcend the well-worn material and Cimino’s overwrought sense of drama.

Anthony Hopkins is one of the best actors of his generation, but his sole collaboration with Cimino as Tim, the Cornell family patriarch, is puzzlingly underwhelming. I’d even go as far as to say that Hopkins is utterly miscast in the role. Tim Cornell is a sophisticated man of taste, enabled by a lawyer’s salary. He’s also a philander and a bad husband/father– when we first meet Tim, he’s in the midst of a messy divorce with his wife, Nora (Mimi Rogers). As the man who must live up to his responsibilities and deliver his family to safety, his arc is theoretically the more interesting one in the film, but Hopkin’s delivery falls flat. I don’t discredit Hopkins with that statement, as he obviously is giving it his all– rather, it’s once again a reflection on Cimino’s uninspiring direction.

The supporting cast doesn’t fare much better. Elias Koteas, who is perhaps my favorite character actor, was the sole highlight of the film for me. He plays Wally Bosworth, Michael’s jittery younger brother. His performance has a greaser-vibe to it, channeling a countercultural energy and spirit that brightens the dour mood every time he appears on-screen. David Morse is equally sympathetic as Albert, the third wheel of the criminal posse and the emotional wild card. Morse plays Albert as an impotently frustrated man who yearns to be smarter than he actually is. This complicates the fact that he has much more of an imposing frame than his two counterparts, which adds a layer of tension where the viewer wonders if he might bite the hand that feeds him, so to speak. Morse conveys depths of information about his character without the luxury of dialogue, which leads me to believe that his is the most accomplished performance in the entire film.

Cimino’s stories are decidedly muscular and brawny– which usually means women are placed predominantly into supporting character roles. As Nora, the Cornell family matriarch, Mimi Rogers is as strong, if not stronger than her husband. This strength initially comes across as a little off-putting during her early squabbles with Tim, but it soon morphs into a rock-solid determination and desire to see her family safely through the ordeal. As Bosworth’s lover Nancy Breyers, Kelly Lynch is appropriately sexualized to match the brutish sensibilities of her paramour. Her feminism is strikingly different from Rogers’– it’s a dainty, delicate feminism that is easily manipulated and broken down. Lynch spends most of the running time delivering her lines in between sobs, but manages to transcend her situation to become one of the key agents of Bosworth’s demise.

Additionally, Lindsay Crouse appears as FBI Agent Chandler, a laughably ridiculous stereotype of your typical gruff police chief. Barking every line like she’s an angry Danny Glover, Crouse is the most curious aspect of the entire movie. She’s doggedly determined, kind’ve like an angry poodle that won’t stop barking. Her approach to policework is dodgy as well, manifested best in the scene where she announces her presence to Tim– the very man she’s trying to save– by pointing a gun to his head. This is the kind of bad, ill-advised performance that people make drinking games out of.

To bring Cimino’s home invasion potboiler to life, he enlists the services of a new cinematographer, Doug Milsome. While shot on 35mm film, this is the first of Cimino’s works not to be photographed in the 2.35:1 aspect ratio. Instead, Milsome composes a 1.85:1 frame that suggests the distinctive air of a second-rate television film. Make no mistake, DESPERATE HOURS is one of ugliest, if not the ugliest, film done by a director otherwise noted for visual flair. The narrower frame takes away from the power of Cimino’s mountain vistas– a major disservice to a film that places itself firmly within the natural beauty of Utah. The colors are natural, albeit subdued and drab. Instead of using well-composed frames to convey narrative and information, Cimino’s restless camera changes angles on an whim by utilizing unmotivated dolly or zoom moves. The deep focus provides for ample opportunities to show off the details of Victoria Paul’s production design, but Cimino takes no such opportunities. Visually, DESPERATE HOURS is an exercise in lazy filmmaking of the highest order.

The music, provided by regular Cimino collaborator David Mansfield, is laughably inappropriate. Criticized as one of the film’s biggest flaws upon its release, Mansfield’s score comes across as an incoherent oddity. The intent is present– it’s obvious that Cimino and Mansfield fancied a big, brassy old-school thriller score that harkened back to the 1950’s– but it feels woefully out of place amidst Cimino’s blandly modern visuals. It barnstorms across the film’s running time, barely ceasing to bludgeon us over the head with proclamations of “atmosphere” and “drama”. As of this writing, this score would become Cimino and Mansfield’s last collaboration. Much like Cimino’s career itself, their partnership started off strong in HEAVEN’s GATE, but quickly descended into depths of incoherence and indulgence that it could not transcend.

DESPERATE HOURS, also the last of Cimino’s collaborations with producer Dino De Laurentiis, still manages to maintain some of Cimino’s thematic preoccupations. Just like Rourke’s Stanley White character in YEAR OF THE DRAGON (1985), his character in DESPERATE HOURS is a Vietnam vet that lives uneasily with his wartime experiences. While this manifests itself in the former film as a vicious volatility, the latter film fosters an ideological, megalomaniacal bent in which Rourke’s character breathlessly pontificates on the sad state of American affairs while providing no alternative solutions.

The gorgeous Rocky Mountain locales provide Cimino with ample opportunity to employ his dramatic mountain vistas that creates a mise-en-scene dripping with detail. But Cimino’s films are infamous for their inaccuracies and one-sided storytelling, and some dramatic details– like the presence of motor checkpoints at a state border– are downright ridiculous. Like his other films, Cimino employs a deliberate sense of pacing, courtesy of editor Peter Hunt. In fact, this is the first film of Cimino’s since THUNDERBOLT AND LIGHTFOOT (1974) to run under two hours– thanks to Cimino eschewing his tendency to dwell unnecessarily on big setpieces. Unfortunately, Cimino and Hunt aren’t able to channel this newfound brevity into anything resembling suspense– a fatal flaw that ultimately sinks the picture.

DESPERATE HOURS is a largely forgettable film, undone by the overcooked dramaturgy of a tragically deluded director. The lack of creative inspiration on display gives the sense that it was a journeyman, for-hire job on Cimino’s part– a lazy bid to get out of “director jail”. Whether he genuinely wasn’t trying, or if his talent has truly left him, it’s impossible to say. It’s clear that everyone involved was trying to do their best work, but they are ultimately a sacrifice to the fire of Cimino’s pretensions. If DESPERATE HOURS is anything, (and there’s a strong case to be made that it’s nothing), it is the final nail in the coffin of Cimino’s once-promising career, and the squandered last chance to reclaim his place amongst the greats.

DESPERATE HOURS is currently available on standard definition (with a terrible sound mix, I might add) via MGM.