Years Active: 1962-present

Alma Mater: UCLA, Hofstra University

Influences: Sergei Eisenstein, Elia Kazan,

Associated Movements: New Hollywood, Film Brats

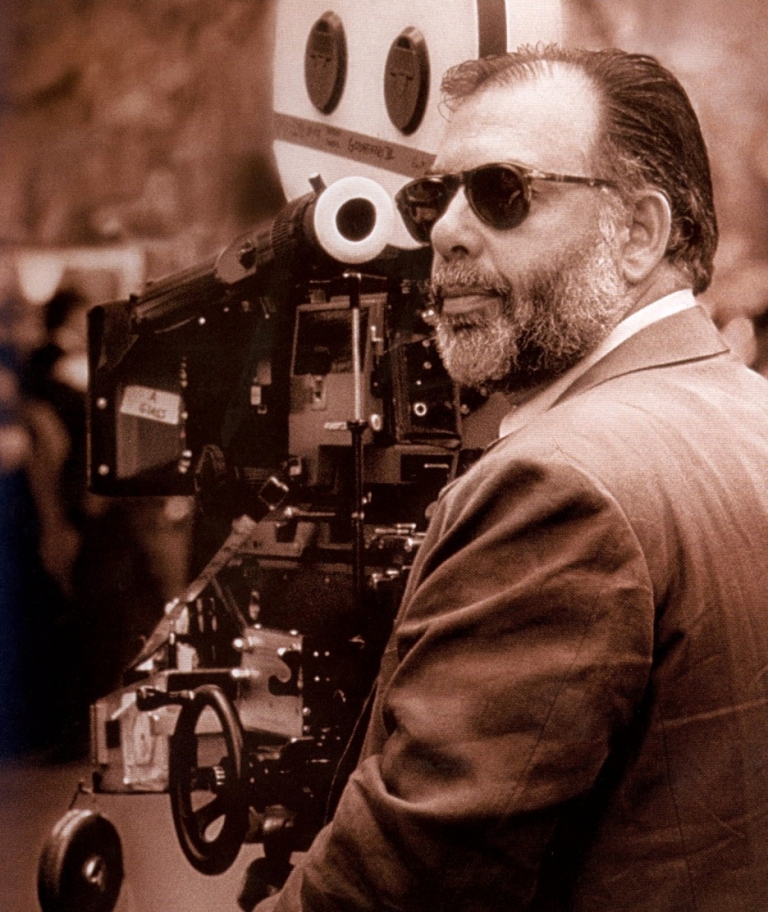

Few figures in the world of cinema cast a shadow as long as Francis Ford Coppola’s. He’s a giant of the art form, with a handful of movies that have redefined film as we know it. His inherent genius, which has cost him considerable grief throughout his career, is abundant enough to be passed down to his offspring. Indeed, the Coppola family dynasty is something of a phenomenon– there’s his daughter, indie darling Sofia Coppola, as well as his filmmaker son Roman (and that’s not even counting more distant family like Jason Schwartzman or Nicolas Cage). His recent films may only have a fraction of the power of his early work, but Coppola’s place in the annals of cinema history is undeniable.

Born in Detroit, but raised in New York City, Coppola found his love for film by way of the theatre. Suffering from polio during his childhood, Coppola entertained himself by putting on puppet shows and dabbling with the family’s 8mm film camera. This led to substantial training in music and theater, capped by a bachelor’s degree from Hofstra University.

It wasn’t until he enrolled in graduate school at UCLA that he began formally studying film. Influenced by the works of Elia Kazan and Sergei Eisenstein, Coppola was a member of the earliest wave of directors to directly benefit from a dedicated filmmaking program. It was during this time that Coppola cut his teeth with shorts like THE TWO CHRISTOPHERS and AYAMONN THE TERRIBLE.

What’s interesting about the beginnings of Coppola’s career is that his work found wide distribution before he even graduated. A full five years before he earned his graduate degree from UCLA, Coppola had already made several feature-length films. Some of these have been lost to time, such as his first work– 1962’s TONIGHT FOR SURE– a softcore comedy meant to titillate rather than entertain.

THE BELLBOY AND THE PLAYGIRLS (1962)

His next work, however, exists in bits and pieces around the internet. Also shot in 1962, THE BELLBOY AND THE PLAYGIRLS was more of an editing job than a directing one. However, recutting and adding new footage to German director Fritz Umgelter’s film MIT EVA FING DIE SUNDE AN earned him a full director’s credit.

The film, shot in black and white, was yet another stag/nudie comedy. The only clip I’ve been able to find, presented above, makes no mention of whether the footage belongs to Coppola or Umgelter. It doesn’t appear to be dubbed, so for the sake of this article I’ll assume it’s Coppola’s.

This brief snippet shows an intimate scene between newlyweds, as the husband tries to cajole his timid new wife into sex. Coppola shoots wide and straight-on, capturing the action dispassionately until we pull back to reveal that these characters are actually actors rehearsing for a play.

It’s a playful move on Coppola’s part to deceive us using only the boundaries of the frame– an effective trick that hints at Coppola’s budding desires to challenge convention and redefine the language of cinema.

BATTLE BEYOND THE SUN (1962)

That same year, Coppola found work as an assistant to legendary B-movie producer Roger Corman. Coppola’s first task under Corman was a daunting one: westernize an existing Soviet sci-fi film entitled NEBO ZOVYOT for American audiences. Coppola’s take on the material, subsequently retitled BATTLE BEYOND THE SUN, became a schlocky monster film, albeit one with the conviction and resourcefulness of a young director with something to prove.

BATTLE BEYOND THE SUN (presented above in its entirety) concerns a space race between a unified Earth’s two latitudinal hemispheres, set in a then-future 1997. Which is hilarious, by the way. When the South Hemis nation attempts to beat the North to Mars and crash-lands on a nearby moon, the two powers must work together and fend off vicious space monsters so they can return to Earth safely.

This film is probably the epitome of Eisenhower-era B-movie cheese. Spacecraft models and props are janky, special effects are laughable, and the limited understanding of actual space travel is preciously quaint. However, it is surprisingly watchable, if only for the glimpses of Coppola’s earliest directorial choices. His largest contribution to the film, besides the dubbing over of dialogue with American actors, was to inject a space monster battle midway through the film. Long before Ridley Scott made the sexualization of aliens cool in ALIEN (1979), Coppola crafted his dueling monsters to resemble vaginas and penises. This was a common characteristic of the lurid films that Corman produced, all of which were churned out rapidly and cheaply to maximize profit.

Ultimately, these films aren’t reliable indicators of Coppola’s growth as a filmmaker. Put simply, they’re glorified editing jobs where Coppola got to re-conceptualize an existing film and conform his edit accordingly. However, they’re fascinating looks into how film school students gained experience in the early days of the institution, when the costly nature of celluloid prompted experience gained via unconventional avenues.

Coppola’s work with Corman would eventually lead to the making and distribution of his first, true feature film. His early works served as important stepping-stones on that path, and now they serve as assurance for up-and-coming filmmakers that even the greats had to start somewhere.