Academy Award Wins: Best Visual Effects

RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK (1981) was a massive commercial and critical hit, with the adventures of Indiana Jones captivating audiences around the world. Naturally, fans were clamoring for a sequel– something Spielberg had never actually attempted before. Indiana Jones’ co-creator, George Lucas, persuaded Spielberg to return, citing the need for a consistent vision across multiple films. Confident in the knowledge that they had a sure hit on their hands before shooting even a single frame of film, Spielberg and Lucas went about assembling their team. Spielberg recruited producing partners Kathleen Kenned and Frank Marshall, while Lucas passed off a story treatment to writers Willard Huyk and Gloria Katz, who were chosen due to their extensive experience with Indian culture.

The film that resulted, INDIANA JONES AND THE TEMPLE OF DOOM (1984), is generally considered to be the darkest entry in the series. While Lucas attributes this to replicating the template set by THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK’s (1980) darker tone, it was also fueled by a dark phase in Lucas’ personal life caused by his divorce from his wife following the completion of RETURN OF THE JEDI (1983). He used the story as a forum to express said darkness, manifesting in ritualistic sacrifices, child slavery, and demonic entities—not to mention people getting their hearts ripped out of their chests (in a poorly-veiled metaphor for Lucas’ own internal state).

It’s 1935, a year before Indiana Jones’ encounter with the lost Ark of the Covenant, and our intrepid hero is in Shanghai dealing with a dangerous crime lord. A business deal between the two at a swanky nightclub goes south, and Indiana (Harrison Ford) barely escapes with his life. Making the escape with him is his trusty child sidekick, Short Round (Jonathan Ke Quan), and a hysterical showgirl named Willie Scott (Kate Capshaw). They board a plane out of China, which is subsequently sabotaged by the crime lord’s underlings and crash lands over India. After seeking directions to Nepal in a rural village, Indiana and company are corralled into recovering the tribe’s precious lost stones, as well as their missing children—abducted into slavery by an evil religious cult operating a temple deep underground. What Indiana doesn’t expect, however, is that his attempts to recover the children and the artifacts will take him on a pitch-black journey into his own heart of darkness.

Harrison Ford, operating at his prime, effortlessly slips back into the fedora and whip. However, he also expands upon the character by creating a version that’s appropriately younger and less experienced (given the fact that the film is technically a prequel). Ford endured excruciating pain throughout most of the production after a back injury, so most of his action scenes had to be completed by a stunt double. Thankfully though, it doesn’t detract from the film at all—Indiana Jones ably delivers on all fronts.

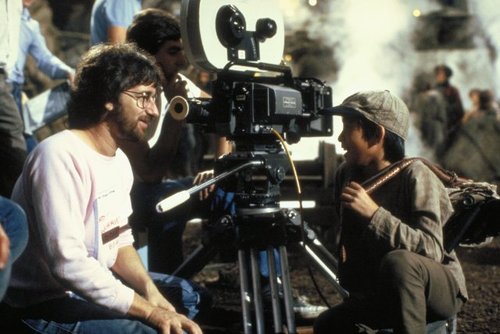

Kate Capshaw’s Willie Scott is the very antithesis of both Jones and RAIDERS’ Marion Ravenwood (Karen Allen). Willie is a blonde, ditzy showgirl with an insufferable vain streak and a tendency to complain about everything. Capshaw, who is naturally very likeable, does a brilliant job depicting someone so inherently unlikeable. However, her performance is overshadowed by the happy fact that her collaboration with Spielberg eventually resulted in their marriage in 1991. As the film was shot in 1984, Spielberg was still a year away from his first marriage to actress Amy Irving, but seeing behind the scenes footage of the Spielberg and Capshaw interacting, it’s clear that they’re totally smitten with each other.

Jonathan Ke Quan makes his mark as Short Round, easily one of the most enjoyable characters in the series. In the wrong hands (aka: Lucas’), Short Round could be a supremely annoying Jar Jar Binks-style character, but Quan succeeds with a winning mix of rakish charm and mischievous innocence. I wish he was my sidekick!

To recapture the warm, exotic look of RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK, Spielberg brings back its cinematographer, Douglas Slocombe. INDIANA JONES AND THE TEMPLE OF DOOM also marks Spielberg’s return to the 2.35:1 aspect ratio format, which helps things look consistent and appropriately epic. Red is used as dominant color throughout, hammering home the fire & brimstone aesthetic of the story. Spielberg also finds several instances to incorporate his signature visual flourishes, like lens flares or an on-screen shooting star.

Despite a substantial increase in production resources, the filmmakers had difficulty in securing location permits from the Indian government—which combined with a series of other mishaps, translated into much of the film being shot on soundstages. This has an adverse effect on the film, whereby the look is contained and distinctively stage-y, not gritty and expansive like RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK was. In other words, TEMPLE OF DOOM looks a little too polished. Editor Michael Kahn does an admirable job sewing it all together, utilizing a swift pace that balances the darkness with lighter, comedic elements peppered throughout. Despite all the doom and gloom, this is a film that doesn’t forget how to have fun.

Just as Spielberg and Slocombe slip right back into the style of INDIANA JONES, so does John Williams effortlessly return to form, expanding on RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK’s iconic, adventurous theme with ethnic flourishes and dissonant choral chants. Some of these flourishes—especially in the Shanghai and India sequences—lean heavily on stereotypical conceptions of those cultures’ music. While it goes a long way towards establishing a geographically-convincing musical palette, it hasn’t aged as well in the context of today’s politically-correct society.

INDIANA JONES AND THE TEMPLE OF DOOM finds Spielberg operating at the peak of his powers as a spectacle director—a peak he still sustains today. Several of the film’s setpieces—the monkey brain dinner scene, the minecart chase, and the rope bridge finale—stand out as some of the best moments in the entire 4-film saga. Not only that, they have become classic, enduring moments in cinema at large; a benchmark that most contemporary action films struggle to meet and rarely achieve. As far as action direction goes, THE TEMPLE OF DOOM is chock full of reference-grade moments.

The success of RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK also allows for some indulgences on Spielberg’s part, as well. The Shanghai nightclub sequence that opens the film provides him with the opportunity to combine two types of films that he’s always wanted to make: the Old Hollywood/Busby Berkeley musical, and the James Bond spy film. Sure enough, TEMPLE OF DOOM starts off with a musical dance number led by Capshaw, which must have surely surprised anyone expecting the same kind of Roosevelt-esque rough rider opening that RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK provided.

Likewise, Indiana channels Sean Connery when he appears in a white dinner jacket and tuxedo while dealing with crime bosses in a cool, collected manner. Complete with hidden guns and shifting power dynamics, the sequence would not be out of place in a Bond film.

Like E.T. THE EXTRA-TERRESTRIAL, Spielberg includes several references to his past work, as well as those of his collaborators and influences. The instance of the Shanghai nightclub being named Club Obi-Wan (after Lucas’ seminal STAR WARS character) is well known, but often overlooked is 1941 star Dan Aykroyd, who makes a brief cameo in the Shanghai sequence. And just like Spielberg cast THE SHINING’s Scatman Crothers for his KICK THE CAN segment in TWILIGHT ZONE: THE MOVIE (1983), here he casts frequent Kubrick character actor Philip Stone (THE SHINING’s ghostly bartender) as a British military officer who comes to Indiana’s aide in the climax.

As expected, INDIANA JONES AND THE TEMPLE OF DOOM was a smash hit when it debuted, but it received decidedly mixed reviews. Some found the darkness of the story to be off-putting and overwhelming, while others simply found it not as enjoyable as its predecessor. For a long time, TEMPLE OF DOOM was generally considered to be the worst film in the INDIANA JONES series— that is, until INDIANA JONES AND THE KINGDOM OF THE CRYSTAL SKULL came about in 2008. Today, TEMPLE OF DOOM simply stands as a solid, albeit flawed entry in the Indiana Jones saga, with an Oscar for visual effects as its strongest selling point.

For all its efforts, INDIANA JONES AND THE TEMPLE OF DOOM did manage to make cinema history. Together with Joe Dante’s GREMLINS (1984), THE TEMPLE OF DOOM is credited with inspiring the creation of the MPAA’s PG-13 rating. Families with young children lured into the theatre criticized it for its pervading darkness and violence, which was graphic but not enough to warrant an R rating. As such, it was deemed that a middle rating was necessary, and Spielberg himself suggested the term “PG-13”. The rise of the PG-13 rating soon became a boon to both Spielberg and the studios, which were able to counter-act years of flagging sales wrought by a growing cynicism among audiences and a wariness of “family-friendly” films. The rating is still extremely relevant today, with many studio tentpole films going to great pains in achieving it and maximizing earning potential for mature subject matter.

INDIANA JONES AND THE TEMPLE OF DOOM, while far from Spielberg’s best film, is highly notable in the context of both his career and his personal life. It was his first full-fledged sequel, and turned Indiana Jones into a bonafide franchise. But more importantly, it was the film where Spielberg met the woman he’d later marry. He had given us the gift of magic and child-like wonder for over ten years now, so it was high time that he finally got to experience some of that for himself.

INDIANA JONES AND THE TEMPLE OF DOOM is currently available on high-definition Blu Ray from Paramount.

Credits:

Produced by: Kathleen Kennedy, George Lucas, Frank Marshall

Written by: Willard Huyck, Gloria Katz

Director of Photography: Douglas Slocombe

Production Designer Elliot Scott

Editor: Michael Kahn

Composer: John Williams