As the twentieth century entered its seventh decade, one of its most prominent cinematic artists was also entering the twilight of his career. After twenty-one feature films, a handful of them among the most celebrated films of all time, director Billy Wilder labored under the growing realization that perhaps his best days were behind him. His influence had been waning for several years, usurped by a new generation of provocative, rebellious auteurs that had grown up watching and learning from his work. He also began losing longtime collaborators to retirement or even the Great Beyond, as he did with longtime mentor and regular producing partner Doane Harrison. Harrison had been one of the most influential figures in Wilder’s artistic development, grooming him with filmmaking values and techniques like “in-camera cutting” that would shape his aesthetic on a fundamental level. After a series of flops and modest hits, and a waning confidence in how many more films they had left in them, Wilder and his writing partner I.A.L. Diamond began dreaming up an audaciously ambitious idea that would serve as one last large-scale effort– a 260 page script about literary detective Sherlock Holmes’ personal life that would be made for $10 million dollars and released as a 165 minute roadshow presentation, complete with intermission.

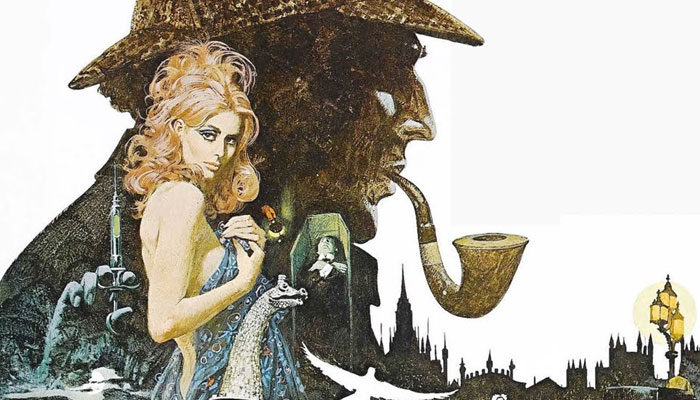

This film was THE PRIVATE LIFE OF SHERLOCK HOLMES (1970), a particularly simple title for a story about exactly that. Set in Victorian-era London and Scotland (roughly 1887) and based on the world-famous characters by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the narrative is split into several separate stories. Both star Robert Stephens and Colin Blakely as Sherlock and his portly assistant Watson, respectively, albeit with a few key modifications made to Doyle’s characters that emphasize their personal vices. The first story finds Holmes and and Watson attending the ballet (and a subsequent high society after-party), only for Holmes to pretend he’s in a homosexual relationship with Watson in order to evade an aging beauty’s request to help her conceive a child. The second, which features iconic genre actor Christopher Lee as Sherlock’s aristocratic brother, Mycroft, resembles more of a traditional Sherlock story wherein he and Watson travel to Scotland to investigate the disappearance of a missing engineer. The case brings them face to face with the Loch Ness Monster, which they eventually discover is an elaborate attempt to disguise the testing of a primitive submarine that had been developed as part of a larger arms-race conspiracy with Germany.

As befitting a grandiose road show presentation, THE PRIVATE LIFE OF SHERLOCK HOLMES was shot in sumptuous CinemaScope Technicolor. Wilder works with cinematographer Christopher Challis for the first (and only) time here, who slathers a gauzy, soft filter over the 35mm film image and exposes it using a broad, even lighting scheme that eschews the evocative shadows Wilder had used so effectively in prior films like DOUBLE INDEMNITY (1944) and SUNSET BOULEVARD (1950). Despite this relatively anonymous visual approach, Wilder nevertheless injects his utilitarian compositional style into the setups, using framing elements like reflections, or classical dolly or crane-based camera movements in lieu of close-ups, cutaways, and other forms of complementary coverage. In recent films like KISS ME, STUPID (1964), Wilder has exhibited a willingness to take inspiration from the younger generation of emerging auteurs– a development also seen in THE PRIVATE LIFE OF SHERLOCK HOLMES when Wilder incorporates zoom lenses as another tool in his coverage-streamlining arsenal. Longtime production designer Alexandre Trauner returns after a brief absence, as does longtime composer Miklos Rozsa after a particularly lengthy one. Rosza’s orchestral score is appropriately ornate, giving itself just enough character to stand on its own while also allowing ample room to share the stage with classical excerpts from Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake.

With its witty banter and clever turns of phrase, THE PRIVATE LIFE OF SHERLOCK HOLMES contains many of the thematic hallmarks of Wilder’s distinct artistic signature. The narrative’s chief motive as a sensational peek into a famous literary character’s personal life allows Wilder many an opportunity to indulge in risqué images and ideas. Beyond the film’s sexual humor– thinly-veiled innuendo and various sight gags that play off Sherlock’s aforementioned same-sex ruse– Wilder eagerly courts controversy by revealing Holmes to be a habitual cocaine user. The narrative is built around the conceit that there’s more to the venerated characters of Sherlock and Watson than readers are familiar with, and as much the film wants to explore what kind of people they were behind closed doors, Wilder’s longstanding fascination with protagonists who identify themselves through the prism of their occupation hampers him in his attempts to explore the characters beyond the intrigue of their jobs. Over the years, his in-depth exploration of the iconography of uniform has expanded to include tangential ideas like costumes and disguises, which this particular film references when Holmes expresses contempt that his signature cap and cloak is a costume that’s been unwillingly foisted upon him by an adoring public who can only see him in one specific way. Finally, the canny observations about class differences that informed Wilder’s previous works are also addressed here, albeit in fleeting fashion. Sherlock and Watson’s successes have brought a fair deal of wealth and renown, enabling them to fit in quite naturally at high society parties and other spheres of aristocratic influence. However, the often-seedy, sordid nature of their investigations keeps their interpersonal communication skills grounded at street-level– Sherlock is just as comfortable chatting up a blue collar gravedigger as he is courting refined socialites.

For nearly all of his career, Wilder had utilized the teachings of Doane Harrison to fuel the creative aesthetic responsible for some of the greatest films in cinema. Consider it ironic, then, that Wilder’s first true editing disaster would occur once Harrison was no longer around to offer guidance. The circumstances of production created a situation in which Wilder couldn’t immediately supervise the cutting of the picture by editor Ernest Walter. This left the post-production process exposed to suffocating mandates from the studio, United Artists. They had suffered a series of misses and flops throughout 1969, and were determined to make THE PRIVATE LIFE OF SHERLOCK HOLMES a hit– at least, by their own misguided standards. This meant paring the original roadshow presentation down to a normal feature experience, excising nearly half of the intended content and reducing the four filmed storylines to two. Wilder was understandably devastated by the hasty neutering of the picture, which he openly eulogized as the “most elegant film he’d ever shot”. In many ways, this was the worst possible thing someone could’ve done to Wilder, hitting him directly in his artistic core. Naturally, the finished product came nowhere near his original vision, and opened to mixed reviews and tepid box office receipts. Some of the excised material can be seen in limited fashion, but the full scope of Wilder’s vision can never be reconstructed as he initially saw it– the negatives containing the deleted storylines were reportedly discarded as soon as the decision came down. THE PRIVATE LIFE OF SHERLOCK HOLMES is an objectively compromised film with little to no chance of a comprehensive reconstruction. There’s no telling if Wilder’s original vision would have even held together had it been left untampered with, but the film’s legacy stands today as one more way station along the path of Wilder’s slow artistic decline.

THE PRIVATE LIFE OF SHERLOCK HOLMES is currently available on high definition Blu Ray via Kino Lorber.

Credits:

Written and Produced by: Billy Wilder and I.A.L. Diamond

Director of Photography: Christopher Challis

Production Designer: Alexandre Trauner

Edited by: Ernest Walter

Music by: Miklos Rosza

References:

IMDB Trivia Section