Inducted into the National Film Registry: 1989

Academy Award Wins: Best Costume Design

An artist’s primary responsibility to the public is to use his or her chosen medium to hold up a mirror to society, to challenge systemic and institutional complacency. Long-established social and moral codes must be questioned and criticized for the greater cultural good. From this mission, a system of checks and balances has emerged, with artists shining a spotlight on the corrosion inherent in our social structures while said social structures respond in kind with regulation and censorship. In the commercial medium of studio cinema, this struggle is particularly acute– in handling a project that costs many millions of dollars and will be seen by many millions of people, filmmakers must walk a fine line between fulfilling their artistic responsibilities while giving their audience and financiers accessible entertainment. Through much of the twentieth century, studio films were regulated by The Motion Picture Code (informally known as the Hays Code), an organization tasked with ensuring that the average American moviegoer wasn’t exposed to indecent or improper material at the cinema. Many Hollywood directors spent the better part of their careers fighting the overbearing Hays Code, some more successfully than others. With his razor sharp wit and disarming mischievousness, director Billy Wilder was particularly well-suited to navigate the tricky contours of the era’s censorship standards– his efforts resulting in some of the most bracing and refreshingly honest films that mid-century audiences had ever seen. His work may seem harmlessly quaint and audience-friendly by modern standards, but in practice his direct challenging of moral complacency bears more in common with the confrontational style of dark mavericks like David Fincher or Stanley Kubrick. The Hays Code would stand until 1968, but its killing blow was struck 9 years earlier when Wilder’s sixteenth feature, SOME LIKE IT HOT (1959), found widespread commercial despite being made without the Code’s approval, rendering the once-tyrannical institution unnecessary and irrelevant.

Wilder was on a career upswing when he made SOME LIKE IT HOT, buoyed by the modest success of 1957’s WITNESS FOR THE PROSECUTION following the twin disappointments of THE SPIRIT OF ST. LOUIS and LOVE IN THE AFTERNOON. Drawing inspiration from a 1936 French film called FANFARES OF LOVE, Wilder wrote the film in collaboration with his LOVE IN THE AFTERNOON co-scribe I.A.L. Diamond– a move that would that cement their working relationship for the rest of both men’s careers. SOME LIKE IT HOT begins in 1929 Chicago: the height of Prohibition and the epicenter of bootleg liquor operations and organized crime. Jerry and Joe (Jack Lemmon and Tony Curtis, respectively) are two struggling musicians who scrounge together a meager living playing in illegal speakeasies. Their friendship dynamic is the stuff of classic buddy comedies: Curtis’ Joe is the handsome straight guy with vision, while Lemmon’s Oscar-nominated performance as Jerry is all manic energy. After witnessing a brutal gangland slaying, Jerry and Joe hastily decide to skip town, catching a one way-ticket down to Miami with a touring jazz band. There’s just one slight problem– the band is girls-only, which means Joe and Jerry have to pose as women if they’re going to escape Chicago with their lives.

Once they arrive in Miami, they’re forced to continue the charade, and not just because the gangsters they’re fleeing have coincidentally arrived in town for their annual Mafia conference. Joe has fallen for one of the girls from the band, a bubbly blonde party girl known as Sugar, but his wooing of her is somewhat complicated by the fact that she only knows him as “Josephine”. Sugar is played by Marilyn Monroe, who in her second and last collaboration with Wilder, provides perhaps the closest glimpse we’ll ever get of the immortal screen icon as she actually was. Sugar, like Monroe, is a porcelain beauty and sexual time bomb, yes– but she’s also wearily disillusioned and regretful of her life choices. Her cheery eagerness to please is an affectation, a mask she wears to hide a profound melancholy and resentment over her image as a sex object and nothing more. Wilder and Monroe had an infamously contentious working relationship during shooting, with Monroe’s pregnancy and pill addiction problems causing her to repeatedly forget even simple lines of dialogue. The Hotel Del Coronado in San Diego was chosen to stand in for Miami in part because it allowed Monroe to reside there during filming, where Wilder could keep an eye on her when cameras weren’t rolling. He was reportedly so fed up with her constant lateness and costly unprofessional behavior that he refused to invite her to the film’s wrap party at his own house. They would eventually make up (even after publicly disparaging each other in publicity interviews), but the damage was irreparable– Wilder and Monroe would never work with each other again. In three years, Monroe would be dead, killed by the very pills that caused her so much trouble on Wilder’s set.

Wilder’s frequent cinematographer Charles Lang returns for their first pairing since SABRINA five years prior, earning an Oscar nomination for his efforts here. The 35mm film was shot in black and white, a notable choice considering that color was just starting to eclipse the monochromatic format in popularity. Monroe’s contract famously mandated that all her films be shot in color, but Wilder was able to overrule her when he demonstrated that the makeup worn by Curtis and Lemmon looked positively nightmarish in Technicolor (1). SOME LIKE IT HOT’s 1.66:1 visual presentation is indicative of Wilder’s utilitarian, minimalist aesthetic. Wide compositions, deep focus, high contrast lighting, and classical camerawork work in tandem to tell the most amount of story in the least amount of individual setups. Wilder uses lighting in particular as a device to differentiate the film’s dual locales– like his earlier entries in the noir genre, Wilder depicts the cold urban landscape of Chicago as a dark, smoky labyrinth of sin and vice. Meanwhile, he depicts Miami as a sun-dappled paradise: sprawling white beaches and elegant palm trees reaching up to clear blue skies. Adolph Deutsch’s jazzy big-band score and Arthur P. Schmidt’s breathless editing tie these disparate locales into a cohesive, manic whole.

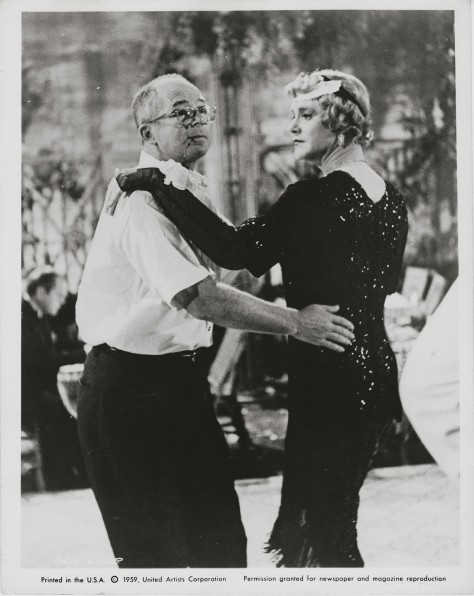

Wilder’s films were already well-known for their provocativeness in an-otherwise chaste moral climate, but SOME LIKE IT HOT courts controversy more aggressively and openly than anything he’s ever done. The film drips with sexual innuendo, finding no shortage of laughs in the various kinks, perversions and delinquencies on display. Joe and Jerry’s cross-dressing is the most visible aspect of the story’s risque nature, enabling veiled allusions to then-taboo subjects like homosexual relationships and singular male infiltration of the female domain (a.k.a “foxes in the henhouse”). Much like he does in his previous films, Wilder orchestrates the plot of SOME LIKE IT HOT as an exploration of characters defined by their class and profession. Joe and Jerry are fish out of water: a pair of starving musicians transported to a world of wealth and leisure. They must wear disguises in order to assimilate into the rarefied air of the wealthy elite– Lemmon doubles down on his female impersonation to manipulate Joe E. Brown’s lovestruck millionaire character to his and Curtis’ advantage, while Curtis himself feels the need to pose as a foppish oil tycoon in order to win Monroe’s affections. The theme of disguise dovetails nicely with Wilder’s recurring use of uniform to define a given character via the prism of his or her occupation. Lemmon and Curtis’ drag wear is highly theatrical– indicative of a what a man thinks a woman dresses like– and because they identify as such to their female colleagues, their costumes become a uniform out of necessity. In the larger sense, Wilder’s approach to uniform doesn’t just stop at the standard-issues duds of cops or hotel bellhops– he abstracts the concept to apply to characters like the mafiosos chasing our heroes. They aren’t all dressed the same, but their wardrobes are similar enough in color, shape, and function as to allow the audience to quickly and easily identify their allegiance.

SOME LIKE IT HOT finds Wilder working at the top of his game, reliably delivering the narrative in the polished form factor we’ve come to expect from him. Yet, it also shows that the old dog is capable of learning new tricks: for instance, the film opens with a riveting cops-and-robbers shootout and chase sequence that reveals Wilder is just as adept at shooting a breathless action sequence as he is a slapstick comedy gag. While some directors tend to grow softer as they slide into their golden years, SOME LIKE IT HOT proves that Wilder’s misanthropic bite is getting even sharper. The film vaulted over a series of obstacles that would a lesser work dead in its tracks: the Catholic Legion of Decency gave it a “Condemned” rating, and the entire state of Kansas found the crossdressing so disturbing that it imposed an outright ban. Seemingly, no regulatory institution– the Hays Code included– could stop SOME LIKE IT HOT’s runaway success. Adored by audiences and critics alike, the film went on to score several Oscar nominations (including two for Wilder’s writing and direction), and is considered by organizations as influential as the American Film Institute to be one of the best comedies ever made. In 1989, Wilder’s comic masterpiece was one of the first films to be inducted into the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry, enshrining his legacy as the filmmaker who dealt the killing blow to a Draconian moral regime and cleared the path for the cinematic provocateurs who would follow in his footsteps.

SOME LIKE IT HOT is currently available on high definition Blu Ray via MGM.

Credits:

Produced by: Billy Wilder

Written by: Billy Wilder, I.A.L. Diamond

Director of Photography: Charles Lang

Production Designers: Ted Haworth, Edward G. Boyle

Edited by: Arthur P. Schmidt

Music by: Adolph Deutsch

References:

1. IDMB Triva page